Tunisialla on ollut merkitsevä juutalainen minoriteettinsä ainakin Rooman imperiumin ajosita. Vuonna 1948 juutalaisväestön arvioitiin olevan 105 000 henkilöä, mutta vuoden 1967 aikaan useimmat Tunisian juutalaisista oli muutanut Ranskaan tai Israeliin ja yhteisö oli supistunut 20 000 henkeen. Vuonna 2012 yhteisö oli edelleen vähentynyt niin että arviolta 150 juutalaista, toisen arvion mukaan noin 1000 henkeä olisi vielä turistisaarella Djerbassa, mikä muodostaisi tämän maan suurimman alkuperäisasukkaitten uskonnollisen minoriteetin.

Tunisia has had a significant Jewish minority since at least Roman times. In 1948, the Jewish population was an estimated 105,000, but by 1967, most Tunisian Jews had left the country for France or Israel, and the population had shrunk to 20,000. As of 2012, however, the population had shrunk to an estimated 150 Jews with another approximately 1,000 on the resort island of Djerba, comprising the country’s largest indigenous religious minority.

- Early History

- Under Islam

- Under the Hafsites , Spanish (1236-1857)

- Mohammed Bey (1855-1881)

- 1881 - Present

- Island of Djerba

- El Kef

Varhaishistoria

Ensimmäisten juutalaisasukkaiten jälkeläisten perimätiedon mukaan heidän esivanhempansa oliat asettuneet tähän Pohjois-Afrikan tienooseen kauan ennen ensimmäinen tempplin tuhoa kuudennella vuosisadalla ( 586 eKr.) . Ranskalainen kapteeni Prudhomme löysi asuma-alueeltaan Hammam Lifsistä vuonna 1883 juutalaisen monumentin ajalta, joka oli ennen kristinuskon leiviämistä sinne. Kun juutalainen altio oli hajonnut, keisari Tiitus lähetti suuret joukot juutalaisia mauritaniaan ja moni heistä asettui Tunisiin. Nämä asukkaat olivat maanviljelijöitä, karjankasvattajia ja kauppiaita. he olivat jakantuneena kahteen heimoon jolla kummallakin oli omat päälliköt ja heidän oli maksettava Roomalle henkirahaa kaksi sekeliä henkilöä kohden. Rooman hallituksen aikana ja vuoden 429 jälkeen kerrassaan suvaitsevaisten vandaalien aikana Tunisin juutalaiset asukkaat lisääntyivät ja menestyivät siinä määrin, että Afrikan kirkon neuvostot olivat sitä mieltä, että on välttämätöntä laatia heitä kohtaan rajoittavia lakeja. Kun Belisarius vuonna 534 karkoitti vandaalit, Justinius I laati vainoista käskykirjeen, jossa juutalaiset luokiteltiin ariaaneihin ja pakanoihin.

Seitsemännellä vuosisadalla juutalaisväestö vahvistui Espanjasta tulevilla maahanmuuttajilla, jotka olivat pakenemassa visigoottikuninkaan Sisebutin ja hänen seuraajiensa vainoja. , pakenivat Mauritaniaan ja asettuivat Bysantin kaupunkeihin. Nämä asukkaat - arabihistorian mukaan- sekoittuivat berberiväestöön ja käännytti monia vahvoja heimoja, jotka harjoittivat juutalaista uskontoa, kunnes Idrisid dynastian perustajan hallitus alkoi. Al kairuwani viitaa, että siihen aikaan kun Hasan vuonna 698 jKr. valloitti Hippo Zaritus nimisen paikan (Bizerta) , sen alueen komentajana oli juutalainen henkilö. Kun Tunis joutui arabien hallinnon alaisuuteen eli Bagdadin arabikalifaatin alaisuuteen, tapahtui toinen arabimaitten juutalaisten muuttovirta Tunisiin. Kuten kaikki muutkin juutalaiset islamilaisissa maissa niin Tunisinkin juutalaiset olivat Umar ibn al-Khattabin määräysten alaisia.

Early History

A tradition among the descendants of the first Jewish settlers were that their ancestors settled in that part of North Africa long before the destruction of the First Temple in the 6th century BCE. Though this is unfounded, the presence of Jews there at the appearance of Christianity is attested by the Jewish monument found by the French captain Prudhomme in his Hammam-Lif residence in 1883. After the dissolution of the Jewish state, a great number of Jews were sent by Titus to Mauritania, and many of them settled in Tunis. These settlers were engaged in agriculture, cattle-raising, and trade. They were divided into clans, or tribes, governed by their respective heads, and had to pay the Romans a capitation tax of 2 shekels. Under the dominion of the Romans and (after 429) of the fairly tolerant Vandals, the Jewish inhabitants of Tunis increased and prospered to such a degree that African Church councils deemed it necessary to enact restrictive laws against them. After the overthrow of the Vandals by Belisarius in 534, Justinian I issued his edict of persecution, in which the Jews were classed with the Arians and heathens.In the seventh century, the Jewish population was largely augmented by Spanish immigrants, who, fleeing from the persecutions of the Visigothic king Sisebut and his successors, escaped to Mauritania and settled in the Byzantine cities. These settlers, according to the Arabic historians, mingled with the Berber population and converted many powerful tribes, which continued to profess Judaism until the reign of the founder of the Idrisid dynasty. Al-Kairuwani relates that at the time of the conquest of Hippo Zaritus (Bizerta) by Hasan in 698 the governor of that district was a Jew. When Tunis came under the dominion of the Arabs, or of the Arabian caliphate of Baghdad, another influx of Arab Jews into Tunis took place. Like all other Jews in Islamic countries, those of Tunis were subject to the ordinance of Umar ibn al-Khattab.

------(Nykyhistorian jaksoa en tänään suomenna, muta asetan vuosiluvut suurilla numeroilla)

1881 - Present

Tunisia was the only Arab country to come under direct and full Nazi occupation during World War II; Morocco and Algeria were governed by Vichy France. When the Nazis arrived in Tunisia in November 1942, the nation was home to some 100,000 Jews. According to Yad Vashem, the Nazis imposed anti-Semitic policies including forcing Jews to wear Star of David badges, fines, and confiscation of property. More than 5,000 Jews were sent to forced labor camps, where 46 are known to have died; an additional 160 Tunisian Jews in France were sent to European death camps. Tunisia, however, was home to Khaled Abdelwahhab, the first Arab nominated for the Israeli Righteous Among the Nations award.

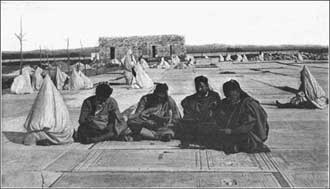

Mourners in the Jewish cemetery in Tunis, c. 1900

By 1967, the country’s Jewish population was fleeing, over 40,000 had left for Israel, leaving 20,000. During the Six Day War, Jews were attacked in riots, and, despite government apologies, 7,000 Jews immigrated to France. "Anti-Jewish sentiments ran high during the [1967] Six-Day War," Mr. Trebelsi recalls. "Some [Tunisian] Jews came under attack but from mobs. It was individual practices really, not systematic".

In 1985, Yasser Arafat’s offices in Tunis were bombed by the Israeli Air Force in retaliation for the murder of three Israelis in Cyprus, an attack that killed over 70 people and leveled the entire PLO complex.

In 1987, a military coup led to the rule of Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali who allowed the Jewish community to thrive despite occasional bursts of anti-Semitic violence. Many prominent Tunisian Jews hailed Ben Ali as their "protector," and in comparison to other Muslim countries, the Jews of Tunisia fared relatively well.

By 2004, the Jewish community in Tunis supported three primary schools, two secondary schools, a yeshiva, and the Chief Rabbi. The Jewish community in Djerba was supporting one kindergarten, two primary schools, two secondary schools, a yeshiva, and a Rabbi. There was also a Jewish primary school and synagogue in the coastal city of Zarzis and the community supported two homes for the aged, several kosher restaurants and four other rabbis.

In January 2011, however, an uprising started by a fruit salesmen in Tunis led to revolution across the Arab world. Ben Ali eventually fled the country to Saudi Arabia and out of the confusion of revolts stepped Islamist parties to take over the government. Though the spiritual leader of the ruling Emnahda party, Rachid Ghannouchi, pledged to support the Jewish community and counter anti-Semitic waves, there have been a number of causes for concern. First, soon after the revolution, a Hamas leader visited Tunis and upon arrival at the airport shouted, "Kill the Jews!" A couple of months after that incident, a crowd of Salafi Muslims gathered in front of Tunis's Grand Synagogue shouting anti-Jewish slogans, led by a cleric who urged Muslims to "rise up and wage a war against the Jews.""Revolution is never a good thing," said Roger Bismuth, a leading Jewish businessman in Tunis who prospered under Ben Ali. "I thought [the Arab Spring] was going to be a mess, and it's even worse than I thought."Ridha Belhadj, chairman of Hizb Tahrir - the Party of Liberation, which calls for a Muslim caliphate to rule the entire Arab world - disagrees that the Jews of Tunisia face any discrimination from the new government. "Why are people exaggerating this problem?" Belhadj asks. "No one has a problem with Jews who live here. They've been here for centuries. They are our neighbors. When they were preaching against the Jews, they meant Israel - not individual Jews here in Tunisia." Rafik Ghaki, a lawyer for a Salafi organization, agrees. "The fact is that when you talk about 'Jews' in Tunisia, you're talking about Zionists. Even the Jews understand that when you talk of Jews, you are speaking only of Zionists."

In April 2012, Tunisian President Moncef Marzouki visited the El Ghriba synagogue to commemorate a decade since the deadly bombing and to ensure that he would do all in his power to protect Tunisia's dwindling Jewish community. Some Jews in the country were unsettled by street demonstrations held in the months priors to the president's visit in which radical Salafi Islamists called on Muslims to kill Jews everywhere.“It is a blessing to live together as Tunisians. Muslims and Jews, our bonds challenge the hatred of the Salafists,” said Perez Trabelsi, president of the El Ghariba synagogue and the Jewish community of Hara Segira, Djerba. “The day-to-day living situation for Jews has not changed since the revolution, and we hope it will never change. We don’t live in fear.”

However, nearly a year and a half later, in October 2013, Yamina Thabet, head of the Tunisian Association Supporting Minorities, said "Tunisian Jews feel in danger, they are really afraid." Thabet's quote came during a visit to the island of Djerba following a number of attacks on the Jewish community in the past few months. Thabet denounced “harassment” by Tunisian security forces and blamed the government, opposition parties and the National Constituent Assembly for the attacks on Jews.

The last Kosher restaurant in Tunisia's capital closed in November 2015, out of concern for the security of their patrons due to terrorist threats. After being warned by the Tunisian government, the owner shut down amid security threats against him and his establishment.

The Island of Djerba

It’s difficult to pin down the exact origins of the Jewish community in Djerba. Depending on different oral histories, the first settlers may have come from Judea about 3,000 years ago, at the time of King David and King Solomon, or at the time of the destruction of the First Temple and the forced Babylonian exile in 586 BCE. They were probably joined by the Jews who fled Jerusalem after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, and others who ran from the Spanish Inquisition. They settled in two separate communities: Hara Kabira (the large Jewish quarter) and Hara Saghira (the small Jewish quarter).According to local lore, the priestly Kohanim who escaped from Jerusalem in 70 CE settled in Hara Saghira, and their descendants still live there today. The Jews dress exactly like their Muslim neighbors - the men in red felt hats, tunics and pantaloons and the women in long dresses and headcoverings, while the younger generation dresses in Western style garb. The only distinguishing feature is a narrow black band at the bottom of the mens’ pantaloons, a sign of mourning for the destruction of the Temple.

7.3. 2016

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar