http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Tunisiavjw.html

Tunisialla on ollut merkitsevä juutalainen minoriteettinsä ainakin Rooman imperiumin ajosita. Vuonna 1948 juutalaisväestön arvioitiin olevan 105 000 henkilöä, mutta vuoden 1967 aikaan useimmat Tunisian juutalaisista oli muutanut Ranskaan tai Israeliin ja yhteisö oli supistunut 20 000 henkeen. Vuonna 2012 yhteisö oli edelleen vähentynyt niin että arviolta 150 juutalaista, toisen arvion mukaan noin 1000 henkeä olisi vielä turistisaarella Djerbassa, mikä muodostaisi tämän maan suurimman alkuperäisasukkaitten uskonnollisen minoriteetin.

Tunisia has had a significant Jewish minority since at least

Roman times. In 1948, the Jewish population was an estimated 105,000, but by 1967, most Tunisian Jews had left the country for

France or

Israel,

and the population had shrunk to 20,000. As of 2012, however, the

population had shrunk to an estimated 150 Jews with another

approximately 1,000 on the resort island of Djerba, comprising the

country’s largest indigenous religious minority.

-

Early History

-

Under Islam

-

Under the Hafsites , Spanish (1236-1857)

-

Mohammed Bey (1855-1881)

-

1881 - Present

-

Island of Djerba

-

El Kef

Varhaishistoria

Ensimmäisten juutalaisasukkaiten jälkeläisten perimätiedon mukaan heidän esivanhempansa oliat asettuneet tähän Pohjois-Afrikan tienooseen kauan ennen ensimmäinen tempplin tuhoa kuudennella vuosisadalla ( 586 eKr.) . Ranskalainen kapteeni Prudhomme löysi asuma-alueeltaan Hammam Lifsistä vuonna 1883 juutalaisen monumentin ajalta, joka oli ennen kristinuskon leiviämistä sinne. Kun juutalainen altio oli hajonnut, keisari Tiitus lähetti suuret joukot juutalaisia mauritaniaan ja moni heistä asettui Tunisiin. Nämä asukkaat olivat maanviljelijöitä, karjankasvattajia ja kauppiaita. he olivat jakantuneena kahteen heimoon jolla kummallakin oli omat päälliköt ja heidän oli maksettava Roomalle henkirahaa kaksi sekeliä henkilöä kohden. Rooman hallituksen aikana ja vuoden 429 jälkeen kerrassaan suvaitsevaisten vandaalien aikana Tunisin juutalaiset asukkaat lisääntyivät ja menestyivät siinä määrin, että Afrikan kirkon neuvostot olivat sitä mieltä, että on välttämätöntä laatia heitä kohtaan rajoittavia lakeja. Kun Belisarius vuonna 534 karkoitti vandaalit, Justinius I laati vainoista käskykirjeen, jossa juutalaiset luokiteltiin ariaaneihin ja pakanoihin.

Seitsemännellä vuosisadalla juutalaisväestö vahvistui Espanjasta tulevilla maahanmuuttajilla, jotka olivat pakenemassa visigoottikuninkaan Sisebutin ja hänen seuraajiensa vainoja. , pakenivat Mauritaniaan ja asettuivat Bysantin kaupunkeihin. Nämä asukkaat - arabihistorian mukaan- sekoittuivat berberiväestöön ja käännytti monia vahvoja heimoja, jotka harjoittivat juutalaista uskontoa, kunnes Idrisid dynastian perustajan hallitus alkoi. Al kairuwani viitaa, että siihen aikaan kun Hasan vuonna 698 jKr. valloitti Hippo Zaritus nimisen paikan (Bizerta) , sen alueen komentajana oli juutalainen henkilö. Kun Tunis joutui arabien hallinnon alaisuuteen eli Bagdadin arabikalifaatin alaisuuteen, tapahtui toinen arabimaitten juutalaisten muuttovirta Tunisiin. Kuten kaikki muutkin juutalaiset islamilaisissa maissa niin Tunisinkin juutalaiset olivat Umar ibn al-Khattabin määräysten alaisia.

Early History

A tradition among the

descendants of the first Jewish settlers were that their ancestors

settled in that part of North Africa long before the destruction of the

First Temple in the 6th century BCE. Though this is unfounded, the presence of Jews there at the appearance of

Christianity

is attested by the Jewish monument found by the French captain

Prudhomme in his Hammam-Lif residence in 1883. After the dissolution of

the Jewish state, a great number of Jews were sent by Titus to

Mauritania,

and many of them settled in Tunis. These settlers were engaged in

agriculture, cattle-raising, and trade. They were divided into clans, or

tribes, governed by their respective heads, and had to pay the Romans a

capitation tax of 2 shekels. Under the dominion of the Romans and

(after 429) of the fairly tolerant Vandals, the Jewish inhabitants of

Tunis increased and prospered to such a degree that African Church

councils deemed it necessary to enact restrictive laws against them.

After the overthrow of the Vandals by Belisarius in 534, Justinian I

issued his edict of persecution, in which the Jews were classed with the

Arians and heathens.

In the seventh century,

the Jewish population was largely augmented by Spanish immigrants, who,

fleeing from the persecutions of the Visigothic king Sisebut and his

successors, escaped to Mauritania and settled in the

Byzantine

cities. These settlers, according to the Arabic historians, mingled

with the Berber population and converted many powerful tribes, which

continued to profess

Judaism

until the reign of the founder of the Idrisid dynasty. Al-Kairuwani

relates that at the time of the conquest of Hippo Zaritus (Bizerta) by

Hasan in 698 the governor of that district was a Jew. When Tunis came

under the dominion of the Arabs, or of the Arabian

caliphate of Baghdad, another influx of Arab Jews into Tunis took place. Like all other

Jews in Islamic countries, those of Tunis were subject to the ordinance of

Umar ibn al-Khattab.

------(Nykyhistorian jaksoa en tänään suomenna, muta asetan vuosiluvut suurilla numeroilla)

1881 - Present

Tunisia was the only Arab country to come under direct and full Nazi occupation during

World War II; Morocco and Algeria were governed by

Vichy France. When the

Nazis arrived in Tunisia

in November 1942, the nation was home to some 100,000 Jews. According to

Yad Vashem, the Nazis imposed anti-Semitic policies including forcing Jews to wear

Star of David badges, fines, and confiscation of property. More than 5,000 Jews were sent to

forced labor camps, where 46 are known to have died; an additional 160 Tunisian Jews in France were sent to European

death camps. Tunisia, however, was home to

Khaled Abdelwahhab, the first Arab nominated for the Israeli

Righteous Among the Nations award.

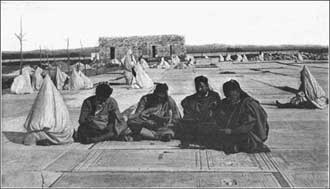

Mourners in the Jewish cemetery in Tunis, c. 1900

|

During the 1950's,

most Jews supported Tunisia's independence movement, led by Habib

Bourguiba, who would become the country's first free president. He

appointed many Jews to prominent positions and guaranteed their

religious and civil rights, however after independence Tunisia’s Jewish

Community Council was abolished by the government and many Jewish areas

and buildings were destroyed for “urban renewal.”

The current

head of the Jewish community in Tunisia, Perez Trebelsi, however,

questions the narrative of some Western historians that Jews were also

persecuted under Tunisian President Habib Bourguiba, the founder of the

republic after independence from France in 1956.

"Bourguiba put all Tunisians on an

equal footing, excluded nationalists, and annulled Sharia-compliant

articles in the constitution like the ones related to polygamy and

inheritance," says the head of the Jewish community in Tunisia, Perez

Trebelsi.

By 1967, the country’s Jewish population was fleeing, over 40,000 had left for Israel, leaving 20,000. During the

Six Day War,

Jews were attacked in riots, and, despite government apologies, 7,000

Jews immigrated to France. "Anti-Jewish sentiments ran high during the

[1967] Six-Day War," Mr. Trebelsi recalls. "Some [Tunisian] Jews came

under attack but from mobs. It was individual practices really, not

systematic".

In 1985, Yasser Arafat’s offices in Tunis were bombed by the

Israeli Air Force in retaliation for the murder of three Israelis in

Cyprus, an attack that killed over 70 people and leveled the entire

PLO complex.

In 1987, a military

coup led to the rule of Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali who allowed the Jewish

community to thrive despite occasional bursts of anti-Semitic violence.

Many prominent Tunisian Jews hailed Ben Ali as their "protector," and in

comparison to other Muslim countries, the Jews of Tunisia fared

relatively well.

By 2004, the Jewish community in Tunis supported three

primary schools, two secondary schools, a yeshiva, and the

Chief Rabbi. The Jewish community in Djerba was supporting one

kindergarten, two primary schools, two secondary schools, a yeshiva,

and a Rabbi. There was also a Jewish primary school and synagogue in

the coastal city of Zarzis and the community supported two homes for

the aged, several kosher restaurants and four other rabbis.

In January 2011,

however, an uprising started by a fruit salesmen in Tunis led to

revolution across the Arab world. Ben Ali eventually fled the country

to Saudi Arabia and out of the confusion of revolts stepped Islamist

parties to take over the government. Though the spiritual leader of the

ruling Emnahda party, Rachid Ghannouchi, pledged to support the Jewish

community and counter anti-Semitic waves, there have been a number of

causes for concern. First, soon after the revolution, a Hamas leader

visited Tunis and upon arrival at the airport shouted, "Kill the Jews!" A

couple of months after that incident, a crowd of Salafi Muslims

gathered in front of Tunis's Grand Synagogue shouting anti-Jewish

slogans, led by a cleric who urged Muslims to "rise up and wage a war

against the Jews."

"Revolution is never a

good thing," said Roger Bismuth, a leading Jewish businessman in Tunis

who prospered under Ben Ali. "I thought [the Arab Spring] was going to

be a mess, and it's even worse than I thought."

Ridha Belhadj,

chairman of Hizb Tahrir - the Party of Liberation, which calls for a

Muslim caliphate to rule the entire Arab world - disagrees that the Jews

of Tunisia face any discrimination from the new government. "Why are

people exaggerating this problem?" Belhadj asks. "No one has a problem

with Jews who live here. They've been here for centuries. They are our

neighbors. When they were preaching against the Jews, they meant Israel -

not individual Jews here in Tunisia." Rafik Ghaki, a lawyer for a

Salafi organization, agrees. "The fact is that when you talk about

'Jews' in Tunisia, you're talking about Zionists. Even the Jews

understand that when you talk of Jews, you are speaking only of

Zionists."

In April 2012,

Tunisian President Moncef Marzouki visited the El Ghriba synagogue to

commemorate a decade since the deadly bombing and to ensure that he

would do all in his power to protect Tunisia's dwindling Jewish

community. Some Jews in the country were unsettled by street

demonstrations held in the months priors to the president's visit in

which radical Salafi Islamists called on Muslims to kill Jews

everywhere.

“It is a blessing to

live together as Tunisians. Muslims and Jews, our bonds challenge the

hatred of the Salafists,” said Perez Trabelsi, president of the El

Ghariba synagogue and the Jewish community of Hara Segira, Djerba.

“The day-to-day living situation for Jews has not changed since the

revolution, and we hope it will never change. We don’t live in fear.”

However, nearly a

year and a half later, in October 2013, Yamina Thabet, head of the

Tunisian Association Supporting Minorities, said "Tunisian Jews feel in

danger, they are really afraid." Thabet's quote came during a visit to

the island of Djerba following a number of attacks on the Jewish

community in the past few months. Thabet denounced “harassment” by

Tunisian security forces and blamed the government, opposition parties

and the National Constituent Assembly for the attacks on Jews.

The last Kosher

restaurant in Tunisia's capital closed in November 2015, out of concern

for the security of their patrons due to terrorist threats. After being

warned by the Tunisian government, the owner shut down amid security

threats against him and his establishment.

The Island of Djerba

It’s difficult to pin

down the

exact origins of the Jewish community in Djerba. Depending on

different oral histories, the first settlers may have come from

Judea about 3,000 years ago, at the time of

King David and

King Solomon, or at the time of the destruction of the

First Temple and the forced

Babylonian exile in 586 BCE. They were probably joined by the Jews who fled

Jerusalem after the

destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, and others who ran from the

Spanish Inquisition. They settled in two separate communities

: Hara Kabira (the large Jewish quarter) and

Hara Saghira (the small Jewish quarter).

According to local lore, the priestly

Kohanim

who escaped from Jerusalem in 70 CE settled in

Hara Saghira, and their

descendants still live there today. The Jews dress exactly like their

Muslim neighbors - the men in red felt hats, tunics and pantaloons and

the women in long dresses and headcoverings, while the younger

generation dresses in Western style garb. The only distinguishing

feature is a narrow black band at the bottom of the mens’ pantaloons, a

sign of mourning for the destruction of the Temple.

7.3. 2016